Ragged Schools, Industrial Schools and ReformatoriesSocial reform was already underway in Britain before The Waifs and Strays Society was founded in 1882. This article looks at how some poor children were dealt with by the Victorian system.

In her discussion of the 'Ragged Classes and Dangerous Classes' Gertrude Himmelfarb briefly outlines the school provision made, 'For the ragged classes ... there were the ragged schools. ... For the perishing classes who had not yet fallen into crime but were likely to do so, there were industrial schools. And for 'juvenile offenders' or 'delinquents' ... who had already committed crimes ... there were reformatory schools.'(1) Ragged SchoolsFor many of the destitute children of London, going to school each day was not an option. There was no such thing as free education for everyone. From the 18th century onwards there had been some ragged schools, however they were few and far between. They had been started in areas where someone had been concerned enough to want to help disadvantaged children towards a better life. The schools were given this name because the children who attended had only very ragged clothes to wear and they rarely had shoes. In other words they did not own clothing suitable in which to attend any other kind of school.

How did they start?In the beginning many of the schools were started by the Churches and were staffed by volunteers. However because of the growing number of children it soon became necessary to have paid members of staff. Many petitions to Parliament for grants were made. The Ragged School UnionDuring the 19th century many people began to worry about the neglected children and so more schools were opened. In 1844 the Ragged School Union was formed with Lord Shaftesbury as its chairman. In the beginning there were just 16 schools connected with it but by 1861 there were 176 schools in the union.

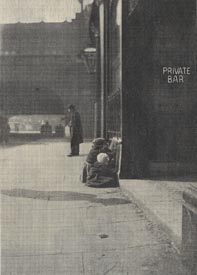

What did the schools provide?As well as giving basic lessons many schools provided food. As time went on some also opened refuges where the children could sleep especially in the extremely cold weather. Even so there were still many areas where there was no provision. In 1853 John Garwood wrote 'In one street ... in the south of London, there now exist 1,500 destitute and criminal juveniles, for whom there is not even a school provided.'(2) Many people believed that by giving the children an education they would be enabled to lead a better life in the future. They would be able to find work to keep themselves and so would not need to steal in order to live. Mr Locke of the Ragged School union called for more help in keeping the schools open. He asked that the government give more thought to preventing crime rather than punishing the wrongdoers. He said the latter course only made the young criminals worse.(3) What did they achieve?Locke detailed all the things achieved by the ragged schools and the difference it had made to the children who attended. He said the schools had been able to find employment for many of the children and they were taught to be careful with their money. As well as learning to read and write they were also given moral guidance. Although so much was being done there was so much more to be done, Locke said they were certain that there were 'thousands upon thousands [of children who] roam the streets unheeded and uncared for, to plunder and do mischief'.(4)

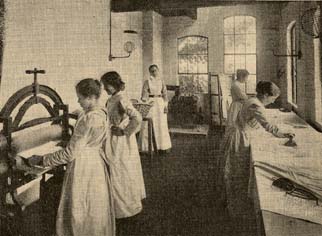

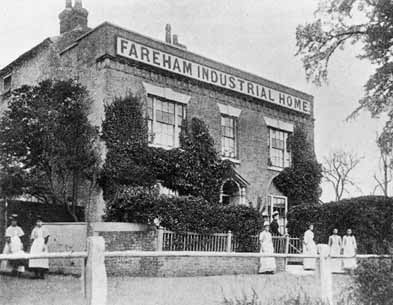

Industrial SchoolsIndustrial schools had two main objects, to instil in the children the habit of working and to develop the latent potential of the destitute child. One of the earliest attempts to start an Industrial feeding School, as they were at first called, was in Aberdeen in 1846. What was their purpose?Industrial Schools were intended to help those children who were destitute but who had not as yet committed any serious crime. The idea was to remove the child from bad influences, give them an education and teach them a trade. It was felt that although the ragged schools were fulfilling a need the provision they provided did not go far enough. The children needed to be removed from the environment in which they had been living. Depending on the circumstances of the child they either attended the school daily or they were able to live in. Daily TimetableThe timetable was quite a strict one, the children rose at 6.00am and went to bed at 7.00pm. During the day there were set times for schooling, learning trades, housework, religion in the form of family worship, meal times and there was also a short time for play three times a day. The boys learned trades such as gardening, tailoring and shoemaking; the girls learned knitting, sewing, housework and washing.

The Industrial Schools ActAt first like the ragged schools the Industrial Schools were run on a voluntary basis. However in 1857 the Industrial Schools Act was passed. This gave magistrates the power to sentence children between the ages of 7 and 14 years old to a spell in one of these institutions. The act dealt with those children who were brought before the courts for vagrancy in other words for being homeless. In 1861 a further act was passed and different categories of children were included:

The act stated the child had to be 'apparently' under the age of fourteen. This was because children often lied about their age if it was advantageous for them to do so. Some children genuinely did not know how old they were. It was not until 1875 that it became compulsory to register births.

The cost of the SchoolsParents were supposed to contribute to the cost of keeping a child in an Industrial School. This often proved impossible to collect because most of the children were homeless. The money had to be found from government sources. As time went on there was quite a lot of unease about the funding mainly because of the rapid expansion of the system. Some people thought it was too big a drain on the public purse. More and more magistrates preferred to send young offenders to the schools instead of prison. From 1870 the schools became the responsibility of the Committee of Education. ReformatoriesThe children who were sent to reformatories were those who had come before the courts having committed more serious crimes. They had usually been arrested many times. The clear distinction between Industrial Schools and Reformatories was that the children sent to Industrial schools were destitute and those sent to Reformatories were juvenile offenders. As the 19th century neared its close people started to realise that all children deserved to receive an education. All children needed care and protection especially those who had been given such a poor start in life and who had received little in the way of care and protection previously. References 1. The Idea of Poverty by Gertrude Himmelfarb (p.379) |